When you first arrive in Italy, you may be surprised to hear people around you not speaking Italian, but a local dialect, or even a different language. The Italian peninsula has a rich history of linguistic varieties. But luckily, you will be able to converse with almost everyone in Italy as long as you know some basics of the Italian language.

This article will introduce you to the language by covering the following topics:

Babbel

Start chatting like a local with Babbel. One of the most popular language-learning apps around, it offers many courses, resources, and live online classes. And, with 13 new languages to choose from, Babbel will have the right course for you.

What languages are spoken in Italy?

The primary language spoken in Italy is, of course, Italian. Even though there are 58 million native speakers of Italian in the country, many local dialects are so complex that locals consider them as native languages in themselves. Several minority languages also co-exist with Italian across the peninsula.

To give you an idea, here are some of the leading minority languages found in Italy:

- Ladin – a Judeo-Spanish language still spoken by around 30,000 people in the Dolomites (Dolomiti)

- Slovene – spoken in northeastern Friuli, close to Slovenia

- German and Bavarian – in the northeastern regions bordering Austria

- French – found in the Val d’Aosta region, across the Alps from France

- Albanian – the Arbëreshë variant of this language is spoken by about 100,000 people, mainly in southern Italy

- Croatian – notably in the regions of Trieste (bordering Croatia) and Molise

- Catalan – about one-third of the population of Alghero, on Sardinia (Sardegna), are proficient speakers of this local dialect of Catalan

- Sardinian – a language related to Catalan spoken daily by over 1 million Sardinians

Where Italian is spoken worldwide

Across Europe, there are 65 million native speakers of Italian. Most of them live (expectedly) in Italy. You can also find them in San Marino, Vatican City, and some parts of Switzerland (mainly Ticino), where Italian is one of the national languages.

Additionally, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Romania, and Slovenia, the Italian language is officially recognized as a minority language.

With large-scale migration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Italian also spread across the Atlantic ocean. As a result, it is now the second-most-common language in Argentina, with 1.5 million speakers. It is also popular in the United States (US), with roughly 17 million people speaking the language.

Origins and history of the Italian language

Italian is part of the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family. It is a Romance language that developed from Vulgar (or common) Latin, the colloquial language of the late Roman empire. Several other European languages (i.e., Spanish, French, Romanian, and Portuguese) also descended from this vernacular.

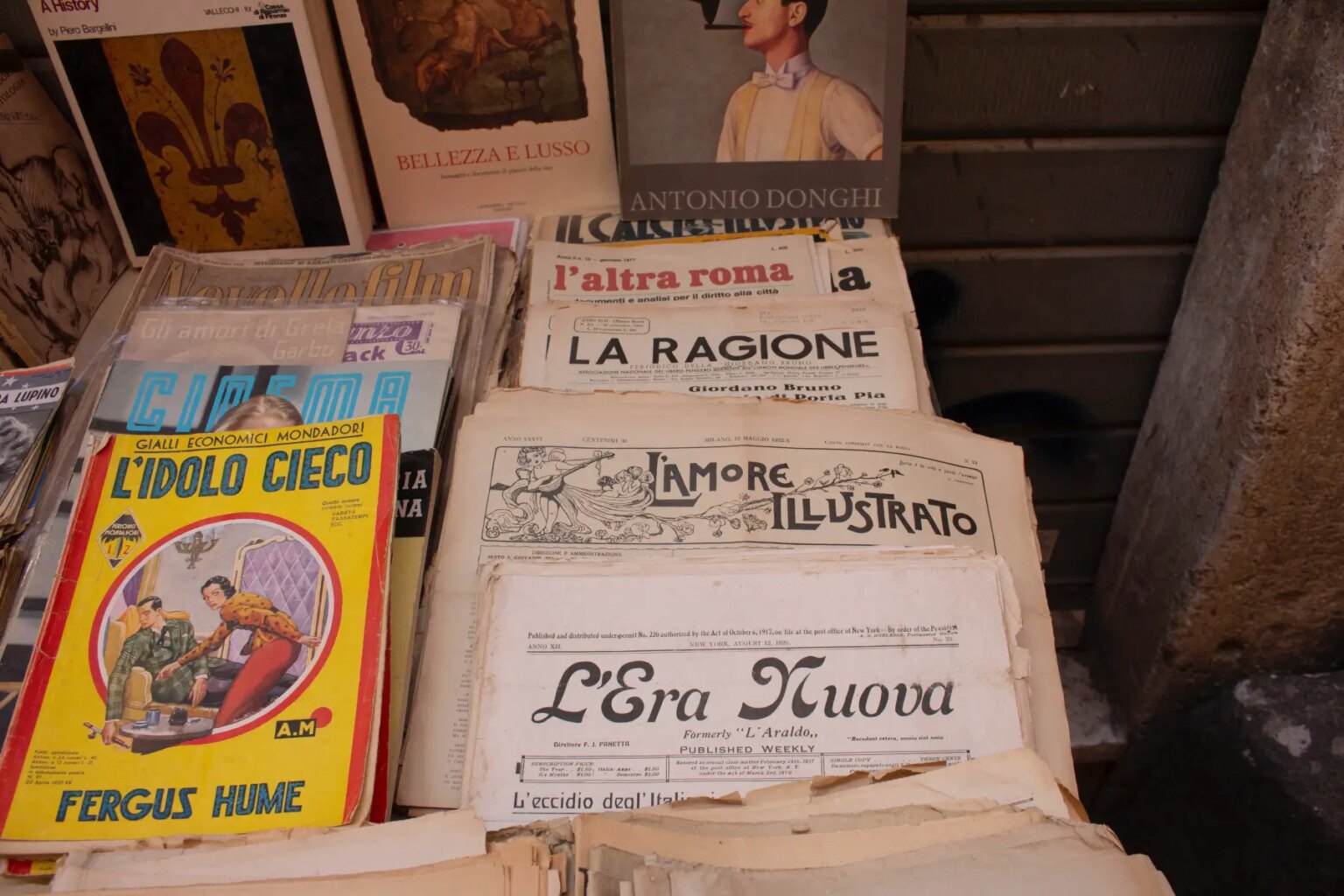

Written examples of what later became Italian are found in legal documents from as far back as the 10th and 11th centuries. But at this stage, it was just one of the hundreds of dialects that populated the peninsula. Latin was still generally used in literature and administrative documents.

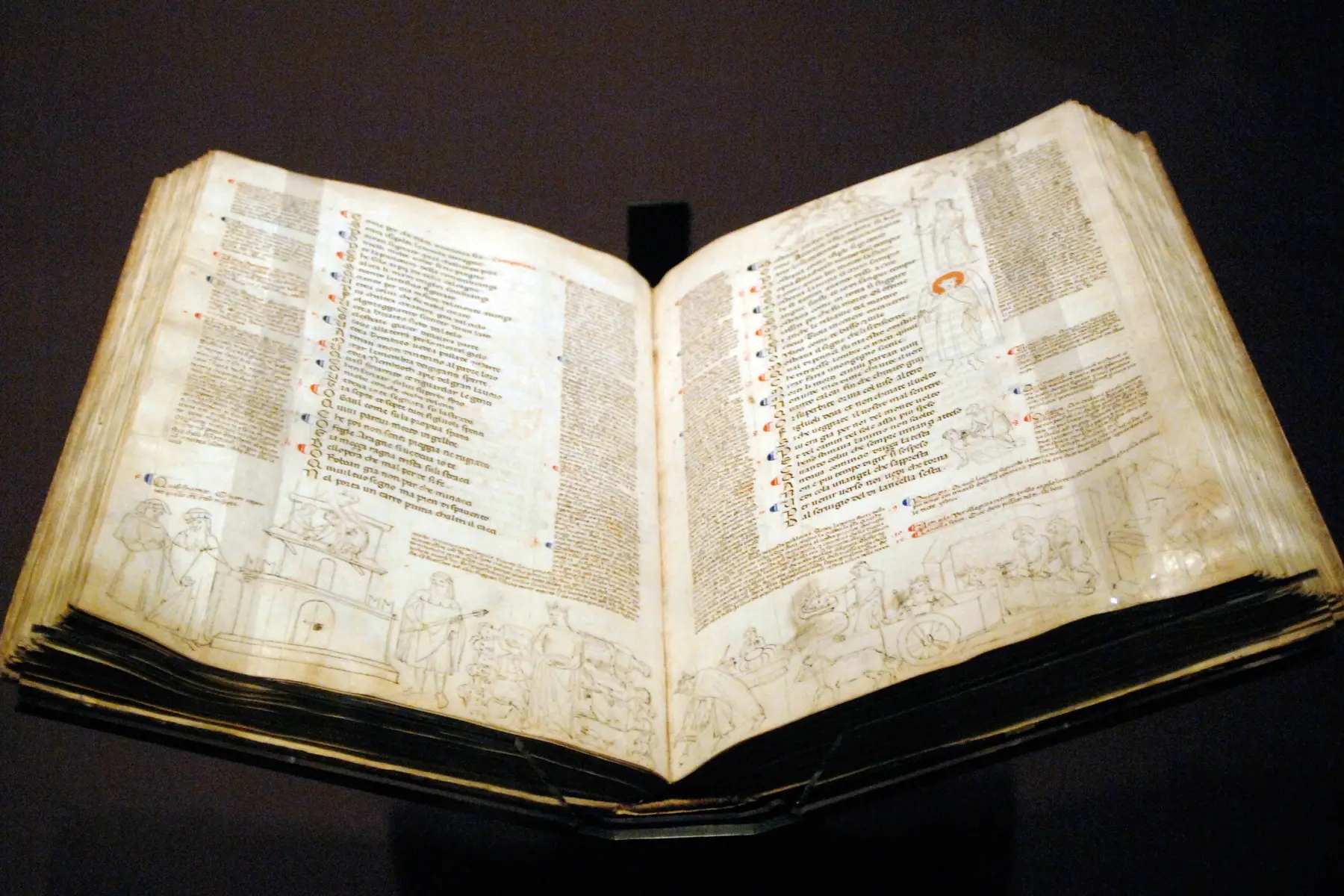

The first great literary work written in the Florentine dialect was The Divine Comedy (La Divina Commedia) by Dante Alighieri in the early 14th century. It is currently kept in the National Central Library of Florence (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze). This work became renowned, which introduced it to the broader population.

In addition to the influence of Dante’s work, the power of Florentine trade and artistic flourishing during the Renaissance likely led to the growing dominance of this particular dialect. Later, during the 15th and 16th centuries, the Tuscan dialect was codified into Italian. It wasn’t until the unification of Italy in 1861, however, that Italian became the country’s official language.

Italian dialects

Standard Italian still co-exists with hundreds of local dialects that also evolved from Vulgar Latin. These fall into the following dialect groups:

- Northern Italian, or Gallo-Italian dialects

- Venetan dialects of northeastern Italy

- Tuscan dialects (including Corsican)

- Mediani dialects of the Marche, Umbria, and Rome (Roma)

- Meridionali dialects of Abruzzo, Puglia (Apulia), Naples (Napoli), Campania, and Lucania

- Meriodionali-Estremi dialects of Calabria, Otranto, and Sicily (Sicilia)

Check out the Europass website to see them all mapped onto lo Stivale (the boot of Italy) and listen to some examples.

Outside of Italy, some people still speak dialectal variations of Italian. For example, the Istrian dialects can still be heard in some areas of the Istrian peninsula in Croatia. Much further away, Brazilian Veneto (or Talian) is an Italian dialect spoken by roughly 500,000 people in southern Brazil.

Italian pronunciation/phonology

Italian uses only 21 letters of the Latin alphabet:

| Letter groups | Letters | Explanation |

| 15 consonants | b, c, d, f, g, l, m, n, p, q, r, s, t, v, z | Consonants are often doubled-up in words, which results in a slight variation in pronunciation |

| One diacritical letter | h | The H doesn’t have a sound but influences the pronunciation of words |

| Five vowels | a, e, i, o, u | Each vowel is almost always pronounced in the same way wherever they individually occur within a word |

It’s important that the letters j, k, x, y, and w are only used in technical terms and symbols, foreign names, and international or specialized terms (e.g., taxi, jackpot, jazz, yo-yo, or web).

Compared to English, it’s much simpler to read Italian once you know how the different combinations of letters sound together, as there is almost no variation in this.

C and G

One difficulty to bear in mind is the pronunciation of the letters c and g. It varies depending on the surrounding letters. Here’s how to use the correct pronunciation for these letters:

| Letter pronunciation | When to use | Examples |

| Hard c (as in cat) | When followed by a, o, u, or any consonant | casa (house), conto (bill), cuanto (leather), crimine (crime) |

| Soft c (as in chair) | When followed by e or i | cena (dinner), cibo (food), cinema (cinema) |

| Hard g (as in glove) | When followed by a, o, u, or any consonant | gonna (garden), galleria (gallery), guarda (to look), gratis (free), ghiaccio (ice) |

| Soft g (as in giraffe) | When followed by e or i | gelato (ice cream), giallo (yellow), gioco (game) |

S and Z

The letters s and z can also have two different pronunciations. S-sounds can either have a hard or a soft pronunciation.

Z-sounds are either voiced (the vocal cords vibrate during pronunciation) or voiceless (the vocal cords do not vibrate).

The general rules are as follows:

| Letter pronunciation | When to use | Examples |

| Hard s (as in zoo) | Between two vowels, or before b, d, g, l, m, n, r, and v | sguardo (gaze), offeso (offended), cosa (what), sbaglio (mistake), musica (music) |

| Soft s (as in house/set) | In cases other than the hard s and always when the s is doubled | stanza (room), ascolatare (to listen), testa (head), pasta (pasta), spechio (mirror), assunto (hired), passata (tomato sauce) |

| Voiced z (the ‘ds’ sound in English – heads) | Usually at the beginning of words or in-between two vowels | zanzara (mosquito), romanzo (novel), zero (zero), zitto (silent) |

| Voiceless z (the ‘ts’ sound in English, as in rats) | Before two vowels in a row, when it appears before the word endings–ezza, -azza, -izza, plus before an l or n | Venezia (Venice), pizza (pizza), agenzia (agency), calzia (socks) |

However, these rules are not set in stone; there are exceptions. Of course, non-native Italian speakers only master these sounds after much practice.

A few more important points about the Italian language

You should also keep the following in mind when learning Italian:

- Most words end in a vowel. Exceptions tend to be monosyllabic words or foreign borrowings (e.g., film (film), camion (truck), nord (north), il (the), non (not), per (for))

- A word where the final syllable is stressed often has an accent on the last letter, like perché (because) or caffè (coffee)

- The r-sound is always rolled, like in Spanish, señorita (woman)

- A q in Italian is always followed by another vowel and is pronounced like the letter k in English

- The letters sc together make a soft sh-sound, like in ‘ship’ or ‘ash.’

Italian grammar

Grammar in Italy is rather simple compared to most other languages. With a bit of effort and practice, you can quickly grasp the essentials.

Nouns

In Italian, nouns are gendered, which means they are either masculine or feminine. This is often reflected in their spelling. When it comes to word endings in the singular, ‘-o’ generally denotes a masculine noun (e.g., il gatto means ‘the tomcat’) and ‘-a’ a feminine one (e.g., la gatta means ‘the queen’ (female cat)). It’s also easier to tell which gender nouns are by looking at their articles.

There are some crossovers in word endings to keep in mind:

| Gender | Singular | Examples | Plural | Examples |

| Masculine noun endings | -o | il gatto (the cat), il disegno (the drawing) | -i | i gatti (the cats), i disegni (the drawings) |

| -e | il cane (the dog), il sole (the sun) | -i | i cani (the dogs), i soli (the suns) | |

| Feminine noun endings | -a | la finestra (the window), la porta (the door) | -e | le finestre (the windows), le porte (the doors) |

| -e | la luce (the light), la carne (the meat) | -i | le luci (the lights), le carni (the meats) |

Naturally (just to keep things interesting), exceptions exist. These make it harder to determine if a noun is masculine or feminine. Some examples include:

- Some feminine nouns end in ‘-o’ (e.g., la mano (the hand))

- Sometimes the plural ending does not change (e.g., le foto/le foto (photograph/s), la moto/le moto (motorbike/s))

- Some masculine nouns end in ‘-a’ (e.g., il cinema (the cinema))

- Some words change gender when they become plural by taking on an ‘-a’ at the end (e.g., il muro/le mura (the wall/s), l’osso/le ossa (the bone/s))

Articles

Italian articles correspond with the gender and the number of a noun. There are seven different types of definite (the) articles:

| Article | Use | Examples |

| il | For singular masculine nouns starting in a consonant, except when using lo (LO) | il cane (the dog), il cielo (the sky) |

| lo | For singular masculine nouns beginning with s + consonant, or starting with z | lo specchio (the mirror), lo zaino (the backpack) |

| la | With feminine nouns starting with any consonant | la donna (the woman), la casa (the house) |

| l’ | Used before masculine or feminine singular nouns beginning with a vowel | l’immagine (the image), l’uomo (the man) |

| gli | With plural masculine nouns starting with vowels, z , gn or s + consonant | gli zaini (the backpacks), gli gnomi (the gnomes), gli studenti (the students) |

| i | With plural masculine nouns starting with consonants other than those above | i libri (the books), i gatti (the cats) |

| le | Before any plural feminine noun | le tazze (the glasses), le case (the houses) |

Indefinite articles

The Italian indefinite (a/an) are as follows:

| Indefinite article | Use | Examples |

| uno | For masculine nouns beginning with s + consonant, or starting with z | uno spuntino (a snack), uno zio (an uncle) |

| un | For all other masculine words | un amico (a friend), un tavolo (a table) |

| una | For feminine nouns starting with any consonant | una madre (a mother), una zia (an aunt) |

| un’ | For feminine nouns starting with a vowel | un’arancina (the arancina), un’ora (the hour) |

When plural nouns are indefinite, they either use no article (like in English) or the partitive (i.e., ‘some’). The singular indefinite nouns in Italian are conjugated into the plural as follows:

| Single indefinite article | Plural indefinite article | Examples |

| un | dei | un bambino (the baby) / bambini (babies)/ dei bambini (some babies) |

| uno | degli | uno zaino (the backpack) / zaini (backpacks)/ degli zaini (some backpacks) |

| una | delle | una ragazza (the girl) / ragazze (girls) / delle ragazze (some girls) |

| un’ | dell’ | un’acqua (the water) / acqua (water) / dell’acqua (some water) |

Adjectives

Adjectives reflect the gender (masculine/feminine), as well as the number (singular/plural) of the corresponding nouns. Adjectives ending in ‘e’ do not vary and always take ‘i’ as the plural.

Examples of adjectives in Italian include:

| Gender | Singular | Plural |

| Masculine noun + adjective | il cane nero (the black dog), lo specchio pesante (the heavy mirror) | i cani neri (the black dogs), gli specchi pesanti (the heavy mirrors) |

| Feminine noun + adjective | la porta nera (the black door), la sede pesante (the heavy seat) | le porte nere (the black doors), le sedi pesanti (the heavy seats) |

Standard Verbs

Most Italian verbs fall into one of three groups, according to the ending of the infinitive form:

- -are verbs – for example, parlare (to talk), giocare (to play), sembrare (to seem)

- -ere verbs – for example, prendere (to take), bere (to drink), tacere (to quieten)

- -ire verbs – for example, finire (to finish), gestire (to manage), capire (to understand)

How you conjugate a verb will depend on which of the above groups it falls into. You simply take the root of the verb, remove the infinitive ending (are/ere/ire), and replace it with another that corresponds to the subject(s) of the verb.

For the present tense, conjugation generally follows this pattern:

| Pronoun | -are verbs (e.g., lavorare (to work)) | -ere verbs (e.g., vivere (to live)) | -ire verbs (e.g., dormire (to sleep)) |

| I (io) You (tu) He/She (lui/lei) We (noi) You (voi) They (loro) | lavoro lavori lavora lavoriamo lavorate lavorano | vivo vivi vive viviamo vivete vivono | dormo dormi dorme dormiamo dormite dormono |

Irregular Verbs

There are always exceptions when conjugating verbs. There’s no way to get around memorizing irregular verb conjugations. The most common ones are:

| Pronoun | Andare (to go) | Venire (to come) | Stare (to be/stay) |

| I (io) You (tu) He/She (lui/lei) We (noi) You (voi) They (loro) | vado vai va andiamo andate vanno | vengo vieni viene veniamo venite vengono | sto stai sta stiamo state stanno |

Stare is an especially important verb since it allows you to create the continuous tense (-ing). So instead of saying: ‘I work’ (lavoro), you can say ‘I am working’ (sto lavorando).

Note that in Italian, you can skip the subject of the verb, since the verb conjugation tells you who you are talking about (e.g., lavoro / io lavoro mean the same).

Interesting facts about the Italian language

With its rich history and evolution, there are plenty of interesting facts about the Italian language.

Here are some to wrap your head around:

- Many Italian words are used to talk about food, but have you stopped to consider their original meaning? For example, biscotto (cookie) is ‘twice cooked’, panna cotta means ‘cooked cream’, and tiramisu literally means ‘pick-me-up.’

- Alongside words like spaghetti and pizza, many other Italian phrases have found their way into everyday English usage. Many of these are linked to performance and music, such as ballerina, diva, opera, scenario, solo, and soprano.

- There are also more somber words like influenza, fiasco, malaria, propaganda, and vendetta, originating from Italian

- You might think of tomatoes as an essential ingredient in Italian cuisine. Yet they were unknown in Italy until the colonization of the Americas. Not recognizing this unusual fruit, the Italians called it pomodoro, which is Latin for ‘golden apple.’

- One of the longest words in Italian has a staggering 26 letters, precipitevolissimevolmente, meaning ‘very, very hastily’

Learning the Italian language in Italy

Learning Italian is one of the best ways to integrate into the local culture. You may want to learn the language for personal development, career prospects, or residency requirements.

From a practical standpoint, speaking Italian will also help you with essential tasks like opening an Italian bank account and navigating the local supermarket. It will even help you understand the healthcare system better, especially when visiting the hospital, doctor, or dentist. If you have school-age children who attend primary school, it may also help you grasp the education system.

If you want to learn Italian, one of the best ways to master some basics is to practice speaking to locals and new-found friends. Italian people tend to be warm, chatty, and eager to socialize, so striking up a conversation as you go about your everyday life won’t be difficult.

On the other hand, taking an immersion course is a great way to become more proficient. Courses take on different forms in Italy – they can be in person, online, in groups, or with a private tutor. You can also find free Italian lessons through your local adult learning center (centro provinciale istruzione adulti – CPIA). Of course, there are also free online resources to help you learn the language, such as the Online Italian Club, a website with free language exercises and lessons.

And if that’s not enough, you can also download some language-learning apps, listen to Italian podcasts or music, and tune in to Italian TV.

So, consider all your options, have fun in the process, and, as they wish someone good luck in Italy, in bocca al lupo!

Useful resources

- RAI school portal – a free online platform with tools to learn Italian (level A1–B2)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (Ministero degli affari esteri e della cooperazione Internazionale) – government website that focuses on the Italian language and culture abroad

- Easy Italian – accessible guides to Italian grammar, idioms, pronunciation, and more