If you’re moving to the United Kingdom with children aged 11–18, you’ll need to consider their education. The country has a variety of schools, and choosing the right one is essential to ensure your child gets the most out of their experience. Read on to find out more about the different types of secondary schools in the UK, which qualifications they offer, and other practical tips:

- The secondary education system in the UK

- State secondary schools in the UK

- The UK school year and timetables

- The UK secondary school curriculum

- The pros and cons of state schools in the UK

- Private secondary schools in the UK

- International schools in the UK

- Applying to secondary schools in the UK

- Graduating in the UK

- Useful resources

The secondary education system in the UK

Secondary education in the UK covers ages 11–18. This divides into stages, which are generally organized in the following way at state schools in England and Wales:

| Key stage | School years | Student age | Qualifications |

| 3 | 7–9 | 11–14 | – |

| 4 | 10 & 11 | 14–16 | General Certificate of Education (GCSEs) |

| 5 | 12 & 13 | 16–18 | Advanced subsidiary (AS) Levels, A-levels, BTEC, International Baccalaureate, etc. |

Northern Ireland follows the same key stages and examination schedule as England and Wales, but secondary education begins in Year 8 and ends in Year 14.

In Scottish schools, secondary education is structured as follows:

| Curriculum stage | School year | Ages | Examinations/assessments |

| Broad general education | First year (S1), Second Year (S2), Third Year (S3) | 11–14 or 12–15 | Scottish National Standardised Assessments (SNSAs) |

| Senior phase | Fourth Year (S4), Fifth Year (S5), Sixth Year (S6) | 14–17 or 15–18 | Nationals 4 & 5, Highers, Advanced Highers |

In the UK, it is mandatory to be in full-time education until the age of 18 (16 in Scotland and Northern Ireland), but students may graduate after their GCSEs at 16 at the end of Key Stage 4. At this point, they can stay at their current school’s sixth form (if applicable), attend college, or start an apprenticeship.

Although UK schools share some similarities, the system differs across England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Because of this, a different government body oversees education in each of these countries:

- England: Department for Education

- Scotland: Scottish Government and Education Scotland

- Wales: Department for Education and Skills (EfES)

- Northern Ireland: Department of Education

There are several different types of secondary schools in the country, each offering different styles of education. These include:

- State schools: Funded and run by local government authorities

- State-funded selective schools: Prestigious public schools which require an entrance exam

- Private schools: Run by private individuals or organizations. Sometimes confusingly known as ‘public schools’ in the UK.

- International schools: Usually follow a curriculum from another country

State secondary schools in the UK

State schools receive financial support from the government. The state funds some fully, while others receive partial subsidies and have more autonomy. The UK government spends around £54 billion each year on secondary education.

In total, 4.3 million students attend 4,172 state secondary schools in the UK. The country has several different types of state schools, and it is important to understand the differences. You might come across:

- Academies and free schools: Run by not-for-profit trusts (such as universities and businesses). They operate independently of the local education authority (LEA) and have more freedom regarding curriculum and management. Some schools choose to become academies, but some must legally convert after receiving an ‘inadequate’ rating from the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted).

- City technology colleges: Independent state schools that focus on science and technology

- Community schools: Traditional state schools maintained by the LEA that follow the UK curriculum

- Faith schools: State schools that follow the national curriculum but with the freedom to teach what they want in religious studies. Anyone can apply to a faith school, but they can choose their admissions criteria.

- Foundation schools: These receive LEA funds but have more freedom in their management

- Grammar schools: State schools that select pupils on academic ability

- Special schools: State schools that focus on special education needs (SEN) and offer tailored support

- State boarding schools: Community schools or academies that offer boarding facilities for a fee

Expat parents may want to vet the quality of potential state secondary schools in the UK before sending their child there. Local educational review bodies provide scores and reports for their schools. Each country within the UK has its own ombudsman, which are:

- England – Ofsted

- Wales – Estyn

- Scotland – Education Scotland

- Northern Ireland – The Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI)

The UK school year and timetables

The traditional school year in the UK runs from September to July (August to June in Scotland) with several breaks, although the local authority generally decides the exact school calendar each year. Usually, state schools have three terms, with one-week breaks approximately in the middle of each, in October, February, and May. There are also Christmas, Easter, and summer holidays, and students have all bank (public) holidays free. Independent schools have more flexibility with their calendar.

Most high schools begin between 08:00 and 09:00 and finish between 15:00 and 16:00, with lunchtime around 12:00 or 13:00. Schools generally provide a midday meal for an extra cost, but students can also bring their own packed lunch.

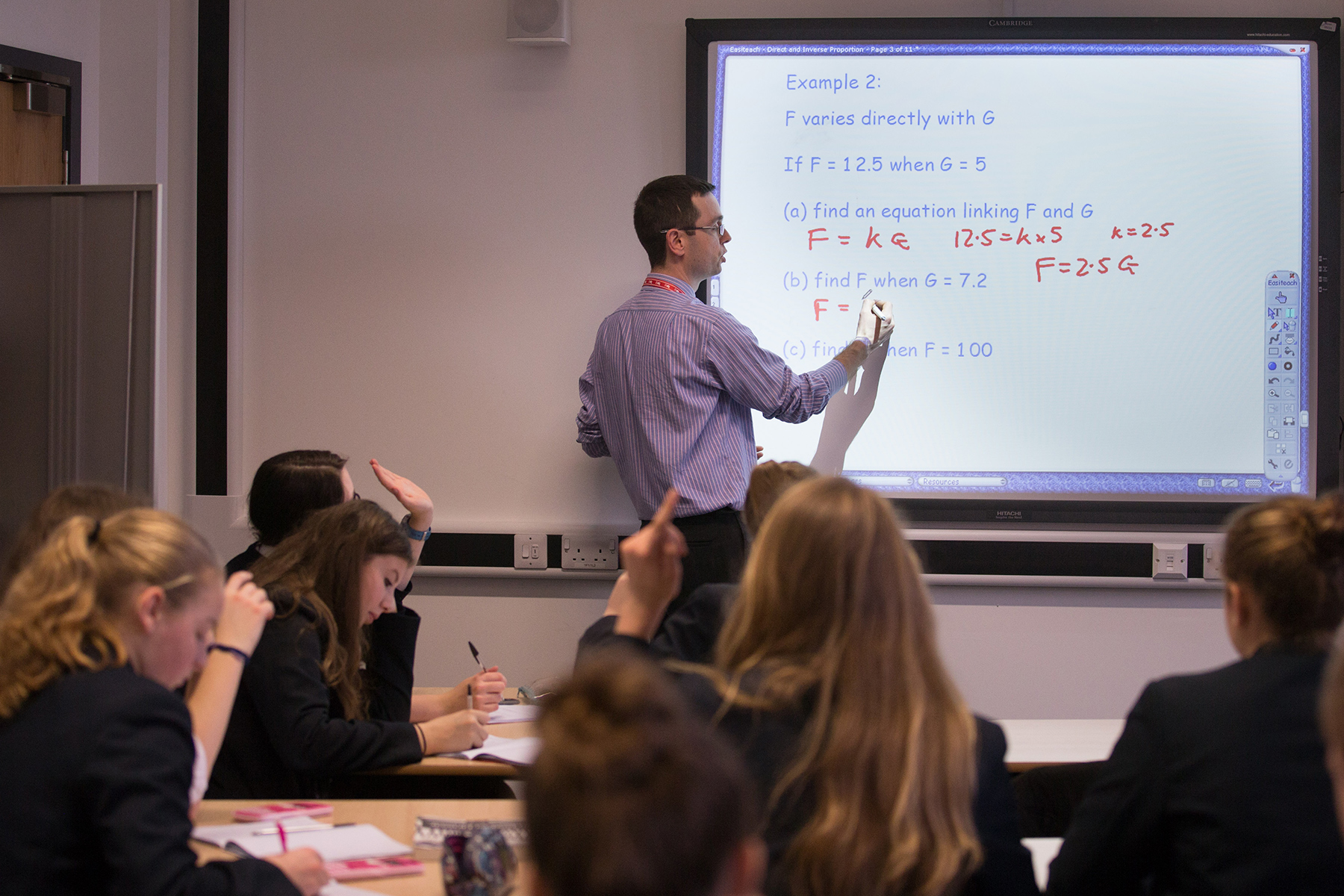

The UK secondary school curriculum

Key stage 3 (England, Wales, Northern Ireland) and Broad General Education (Scotland)

England and Wales

Schools in England and Wales follow the UK national curriculum. In years 7–9, lessons consist mainly of mandatory subjects, which are as follows:

- English

- Maths

- Science

- History

- Geography

- Modern foreign languages

- Design and technology

- Art and design

- Music

- Physical education

- Citizenship

- Computing

There are no formal examinations at the end of year 9 in England and Wales, but schools may carry out assessments throughout the year or at the end of terms.

Some schools in Wales also offer Welsh-medium education, where subjects are taught mostly in the country’s native Celtic language.

Scotland

In Scotland, students from S1–S3 receive a broad education based on eight curriculum areas:

- Languages

- Expressive arts

- Health and wellbeing

- Numeracy and mathematics

- Religious and moral education

- Sciences

- Social studies

- Technologies

A few schools in Scotland provide Gaelic-medium education, in which students learn their subjects in Scottish Gaelic, with English as a second language. Students complete Scottish National Standardised Assessments (SNSAs, Measaidhean Coitcheann Naiseanta airson Foghlam tron Ghàdhlig – MCNG in Gaelic) online at the end of S3. However, these assessments identify areas of strength and improvement rather than providing a passing or failing grade.

Northern Ireland

Meanwhile, Key stage 3 in Northern Ireland offers the following main curriculum areas and subjects:

- Language and Literacy: English, Irish (in Irish-speaking schools), and Media Education

- Mathematics and Numeracy: Mathematics and Financial Capability

- Modern Languages: An official language of the European Union (other than English or Irish)

- The Arts: Art and Design, Music, and Drama

- Environment and Society: History and Geography

- Science and Technology: Science and Technology and Design

- Learning for Life and Work: Employability, Local and Global Citizenship, Personal Development, and Home Economics

- Physical Education

- Religious Education

Students in Northern Ireland are assessed using the Levels of Progression (LoP), which provide ‘can do’ statements rather than specific grades. Schools generally measure students’ levels on an ongoing basis. There are two post-primary Irish-medium schools in Northern Ireland.

Key stage 4 and Senior phase

England, Wales, and Northern Ireland

In years 10 and 11, students at state secondary schools in the UK usually prepare for the General Certificate of Education (GCSE) exams. During these two years, they study a selection of mandatory subjects, which include:

- English – 2 GCSEs: English language and English Literature

- Maths

- Science – Either a combination of separate Biology, Chemistry, and Physics GCSEs or ‘Combined Science,’ a double GCSE with aspects of each subject area

In many schools, Religious Studies (RS), Computer Science, and Physical Education are also required.

Students also choose ‘options,’ additional subjects which bring the total number of GCSEs studied to at least five. Most students take nine or ten. While provision varies depending on the school, optional GCSEs may include:

- Languages: Modern or Ancient. The most popular language GCSEs are Spanish, French, and German, but some schools offer others, such as Chinese (Mandarin), Italian, and Latin.

- Humanities: Including History and Geography

- Arts: Such as Music, Drama, Art and Design, or Media Studies

- Technology: Examples include Electronics, Design and Technology, or Food Preparation and Nutrition

Welsh schools also offer GCSE Welsh Language and Welsh as a Second Language. Similarly, GCSE Irish is available in Northern Ireland.

In England, GCSEs are graded on a scale of 9–1, with 9 being the highest. Grade 4 is a ‘standard pass,’ while grade 5 is a ‘strong pass.’ Many subjects are divided into ‘higher’ and ‘foundation’ grades, where higher papers cover grades 9–4 and foundation covers grades 5-1.

On the other hand, in Wales and Northern Ireland, GCSEs usually follow an A* to G scale unless the school uses an English examination board. A* is equivalent to a 9, and grade C roughly matches grades 4–5 in England. In both systems, a U is an ‘unclassified’ failing grade.

Most schools in Wales also teach the Welsh Baccalaureate (levels 1 and 2), a skills-based qualification that complements GCSEs.

Scotland

In S4, students in Scotland begin what is known as the ‘Senior phase.’ During this time, their subject areas are the same as in their first three years of high school, but they choose around six subjects to focus on. Maths and English are usually mandatory, but schools can decide whether students must take science.

The qualifications for this stage, National 4s and 5s, are roughly equivalent to GCSEs and usually include an external examination.

Education post-16

England, Wales, and Northern Ireland

Once students have their GCSEs, they have several options. Although pupils in England must stay in education or training until they are 18, Welsh and Northern Irish students might enter employment at this stage. Meanwhile, some of the most popular choices for further education and training are as follows:

- Academic qualifications such as A-levels and the International Baccalaureate (IB). For A-levels, students choose 3–4 subjects to study in more detail. These qualifications are usually in preparation for university. Welsh students take the Level 3 Advanced Baccalaureate alongside their A-levels.

- Vocational and technical qualifications, including Business and Technology Education Council (BTEC). Students can take these instead of or alongside GCSEs and A-levels.

- An apprenticeship to learn a skilled trade

You can read more about A-levels and vocational options further down the page.

Scotland

Scottish students can finish their secondary education once they have taken their Nationals. However, most stay on to sit their Highers in Fifth Year. These qualifications are necessary for university.

Some students stay for an extra year, S6, where they can take Advanced Highers and begin university in the second year. Unlike in England, Scottish undergraduate degrees are usually four years long rather than three.

Students usually study four or five Higher subjects, which consist of core mandatory subjects and additional options. Meanwhile, there are fewer Advanced Higher courses available, but pupils generally study two or three.

Assessment for both qualifications may consist of final exams, coursework, or other projects. Students receive a grade between A and D, with A being the highest, or ‘No Award’ if they fail.

The pros and cons of state schools in the UK

It can be tricky for internationals to decide which type of secondary school to send their children to. If you’re debating whether to send your child to a state school, it’s worth weighing up the pros and cons.

First, the advantages. As most teenagers in the UK attend state school, they’ll likely integrate better with the local culture. Furthermore, more of these schools are available, so you might have more choices. Perhaps the biggest advantage that state schools offer is their price. There are no fees for sending your child to a state school, but you may need to factor in costs for textbooks, trips, and uniforms.

Local expert

Sarah Fairman

Insider Tip

Most British secondary schools, state or otherwise, have a mandatory uniform, which usually comes at an additional cost. Dress codes vary, but some can be very strict – most prohibit trainers, and many have stringent rules about make-up, accessories, skirt lengths, and other aspects of personal appearance.

However, there are some downsides to public education in the UK. State schools generally score lower than private schools in GCSE and A-level results, and class sizes are usually much larger.

Private secondary schools in the UK

Private schools in the UK are also known as independent or public schools. There are 261 independent ‘senior schools’ in the country, offering education to Year 7 and above, and 495 mixed-age schools. According to the Independent Schools Council (ISC), 336,907 secondary-age students attend an ISC school. Around 6.6% of all pupils in such schools are non-British.

These schools generally have more freedom in their teaching methods than state schools. However, many adhere to the UK curriculum and tend to have more pupils attaining top grades at A-level. They also usually have top-tier facilities, a wide range of extracurriculars, and the highest university acceptance rate of any type of school.

However, these advantages come with a hefty price tag. The average term fee for senior day schools was £5,854 in 2023, with the majority charging between £3,000 and £5,500. Some schools offer scholarships and bursaries – around 34% of students receive at least some assistance with their fees.

International schools in the UK

International schools follow the curriculum of their choice, often associated with a specific country. They can be a good choice for expat children, as you may be able to find one that offers a familiar education system and qualifications. Many offer qualifications that are recognized across the world, such as the International Baccalaureate (IB). International schools in the UK include:

- ASC Cobham International School (American/IGCSE/IB)

- College Français Bilingue de Londres (French/Brevet)

- Dwight School, London (IB)

- EIFA International School (French/Brevet/IGCSE/IB)

- International School of London (IB)

- Instituto Español Vincente Cañada Blanch (Spanish)

- École Jeannine Manuel (French/IB)

- Deutsche Schule London (German)

- Rikkyo School in England (Japanese)

These schools may be a more desirable option if you’re only staying in the UK for a short period or if your child intends to study outside the UK after graduating from secondary school.

The International Baccalaureate (IB) in the UK

In the UK, 76 private and 55 state secondary schools offer the IB diploma. This prestigious high school qualification is available worldwide, so many expat parents choose to send their child to a school that provides it to ensure consistency. Additionally, it is accepted by many universities in the UK and abroad.

However, as so few UK schools offer the IB, you may find your options limited compared to A-levels. Furthermore, the schools offering the IB in the UK are all located in England, Wales, and Scotland, and no Northern Irish schools teach it.

Applying to secondary schools in the UK

State school applications

Each council in the UK has an application form for local secondary schools. You’ll usually need to apply between September and October for your child to begin secondary school the following September. Check your local council’s pages to find out about each one’s facilities, rankings, and teaching styles.

When applying in England and Wales, parents often list three or four schools (six in London) in order of preference. State schools in the UK are generally over-subscribed, so although non-selective schools do not require students to pass exams, they usually award places based on certain admissions criteria. These might include:

- Proximity to the school

- Having a sibling at the school

- Other educational needs

In Scotland, children are generally allocated a place at a school in their catchment area. Parents can make a ‘placing request’ to another school if they are unhappy with the designated one. Meanwhile, in Northern Ireland, parents should list at least four preferred schools during the application.

Faith and grammar schools have additional requirements. For example, students who apply to grammar schools must pass the 11+ exams – you can find out more about registration and taking these tests from your prospective schools. Faith schools may require evidence of religion, such as a baptism certificate or letters from religious leaders.

When applying, you’ll usually need the following documents:

- Child’s ID to prove legal name and date of birth (valid passport, UK birth certificate, or documents from the National Asylum Seeker Service)

- Completed application form from the Local Authority or school

- Proof of address, such as a mortgage/tenancy agreement or utility bill

- Emergency contact information

- Proof that you have parental responsibility for the child

Private school applications

If you wish to send your child to a private school, including an international one, you’ll deal with the school directly. The application process can vary significantly from one institution to another, and there are additional considerations.

For example, some schools require interviews with parents or entrance exams for prospective students. They may also request a reference from your child’s current school. Furthermore, the biggest considerations are the costs involved – you may need to prove your income (if no scholarships apply) and pay an application fee.

Applying to school from abroad

If applying to a UK secondary school from abroad, there’s even more to consider. You must make sure your child is permitted to enter the country, either because they have a right of abode or a valid visa.

While you’ll still need to provide proof of a UK address, if you haven’t secured accommodation by the deadline, contact the council you’ll be moving to and explain your situation. If you can provide a letter from your employer showing your intention to move to the area, this may help your case.

You can also apply ‘in-year’ if you move to the country during the school year. However, bear in mind that a place at your preferred school may not be available.

Graduating in the UK

England, Wales, and Northern Ireland

Students at state schools take most of their GCSE and A-level exams in May and June, at the end of the academic year. In many cases, lessons finish a couple of weeks before the exams for ‘study leave’, a period dedicated to preparation and revision.

Although GCSE exams occur at the end of Year 11 (Year 12 in Northern Ireland), many students sit mock exams in Year 10 to gauge their current level and provide predicted grades.

Students sitting A-levels may take two qualifications: Advanced Subsidiary (AS) levels and A-levels. AS-levels are generally taken in Year 12 (Year 13 in NI), and A-levels in Year 13 (Year 14 in NI). In England, AS-levels and A-levels are two separate qualifications, so some schools do not offer the former, and students go directly to the more advanced certificate. However, in Wales and Northern Ireland, AS-levels contribute towards the final A-level grade.

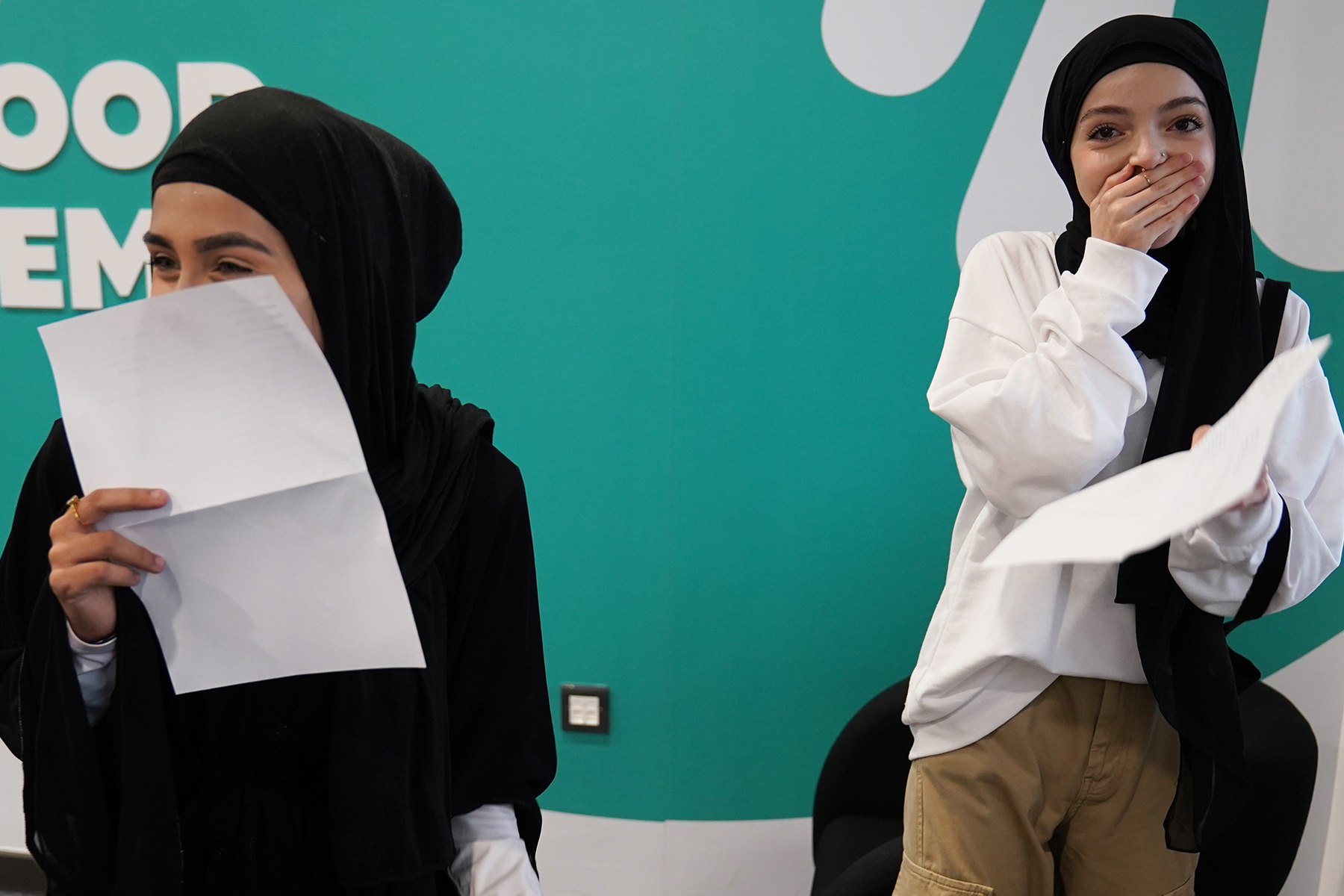

Once students have finished their exams, they await the outcome: A-level results usually come out on the second Thursday of August, and GCSEs a week after. State schools rarely have a graduation ceremony – students tend to go to school in the morning to pick up an envelope containing their results and celebrate with friends or family afterward. However, some schools organize leavers’ events, proms, or awards ceremonies.

You can read about the options for post-GCSE education above. Meanwhile, A-level results determine whether a student will attend university and which one they achieve a place at.

Local expert

Sarah Fairman

Insider tip

If you don’t get the A-level results you wanted, all is not lost! Check on UCAS to see if one of your university choices has accepted you anyway. Otherwise, get on the phone as soon as possible, as you may be able to find another university place through clearing.

Scotland

Students in Scotland usually take their final exams (Nationals, Highers, and Advanced Highers) in April and May and receive their results in early August. Like in the rest of the UK, there is usually no formal graduation ceremony, but many students celebrate finishing their school education.

IB exams and graduation

Exams for the IB take place at the same time in the UK as in the rest of the world – usually from April to mid-May, although some schools and retake candidates might take exams in the November Session (October–November).

Results for the May Session are released on 6 July every year, while November Session results come out on 3 January.

International schools and other private schools may have different qualifications, exams, and results procedures – check with them to find out the important dates.

Applying to university

Students in the UK who wish to continue studying to earn a degree usually apply to university before finishing secondary school. They apply through the country’s centralized university application system: the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS).

The UCAS application includes:

- The student’s choice of four or five university courses

- Personal details

- Education (and employment) history

- A personal statement detailing why they have chosen the course, their interests, and achievements

- A reference from someone who knows the student in a professional or academic capacity, such as a teacher or former employer

Secondary school students submit this application by mid-January (or mid-October for medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine, or courses at Oxford and Cambridge). They then wait to hear whether the university has accepted their application and what their required grades are, if any. If more than one university offers them a place, they choose a firm (first choice) and an insurance (backup choice) offer to accept.

On results day, UCAS sends the students’ results to the university. If they have met the required grades, the offer changes to ‘unconditional,’ and their place is secured. Students who haven’t achieved the grades they need or got better results than expected can apply for a place through clearing from July to September.

Trade schools in the UK

Post-16, students in the UK also have the option to gain vocational skills and qualifications. There are several types available.

England, Wales, and Northern Ireland

In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, students can take the following qualifications after they finish their mandatory education:

- Business and Technology Education Council Qualifications (BTECs) – These are given at levels 1–7, with Levels 1 and 2 being equivalent to a GCSE and Level 3 comparable to an A-level. They consist of coursework, practical assessments, and examinations, and many universities recognize them in applications.

- T-levels – T-levels were introduced in 2020 as a technical qualification equivalent to three A-levels. They involve learning combined with a work placement. Although students generally need a Grade 4 in their English and Maths GCSEs, some courses include a transition program or additional help for students who did not achieve this grade.

- Apprenticeships – An apprenticeship involves training for a specific job, and apprentices spend 80% of their time in the workplace and 20% in off-the-job learning. Level 2 apprenticeships are equivalent to a GCSE qualification, while Level 3 matches A-level standard.

- National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) – Practical qualifications relating to a specific field of work. They are assessed through observation. Level 1 is equivalent to GCSE grades 3–1, Level 2 to GCSE grades 9–4, and Level 3 to A-level.

Depending on which qualification you choose, the application process varies. Sixth-forms and colleges often offer BTECs and T-levels, but you should visit the UK Government website for information on apprenticeships. Meanwhile, colleges, training centers, and workplaces provide NVQs, and you can also find online options.

Scotland

Students in Scotland who wish to take a vocational qualification have the following options:

- Foundation apprenticeships – These are taken in S5 and S6 and give students work-based learning opportunities. They function as a pathway to Modern or Graduate Apprenticeships and are equivalent to a Higher.

- Modern apprenticeships – These combine employment and training, meaning students can earn a salary while learning and working. They last 1–4 years.

- Graduate apprenticeships – These types of apprenticeships provide work-based learning and include part of the time studying at university. Graduate apprentices can earn an Ordinary or Master’s Degree.

- Scottish Vocational Qualifications (SVQs) – Comparable to NVQs in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, these are a good option for students who want to earn a qualification based on a specific job.

Useful resources

- Apprenticeships – details on how to apply in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland

- The Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI) – Northern Ireland’s educational standards body

- Education Scotland

- Estyn – education and training inspectorate for Wales

- Ofsted – Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (England)

- UCAS – information on university applications

- UK Government – The National Curriculum

- UK Government – School applications for overseas children