The driving force of Europe

Expatica Germany

Expat guides

Explore

Editor's picks

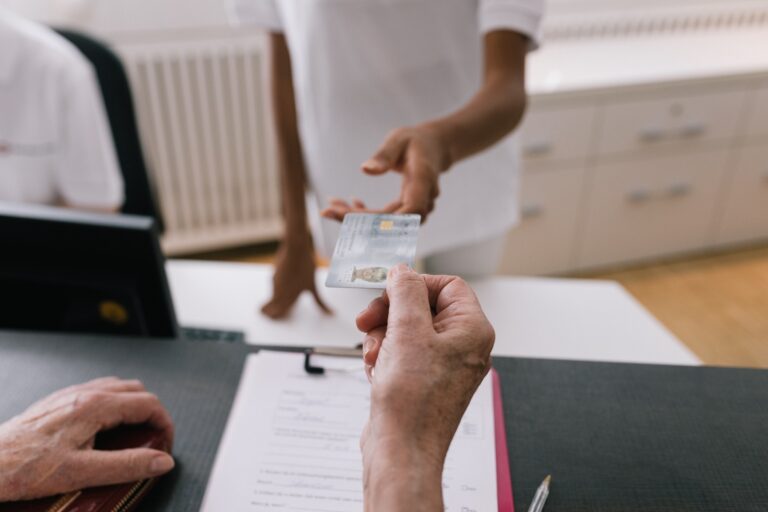

Health insurance in Germany

Explore the best expat health insurance options for Germany, including eligibility for public insurance (GKV) and private coverage (PKV).

Read More

Dating in Germany

Navigate the world of dating in Germany as an expat by understanding the local dating culture, etiquette, faux pas, and more.

Read More

The German education system

Learn about the German education system, including types of schools, financial aid, educational support, homeschooling, and graduating.

Read More

Germany Salary Calculator

Find out what you'll take home after tax